Vorple in depth

Back in the days when home computers first entered consumer markets there were many competing companies selling computers that weren't compatible with each other. To maximize the amount of potential customers Infocom had to solve the problem of programming and distributing their games to a wide array of computers with varying specifications and limitations.

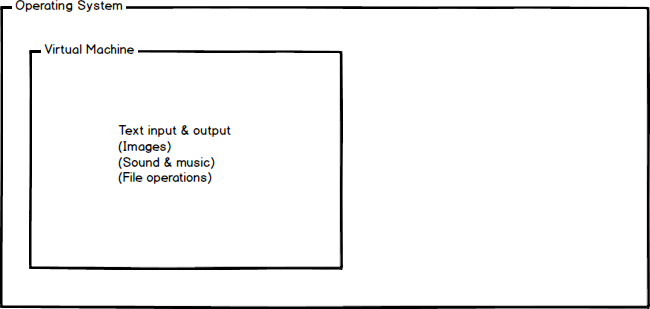

The solution was to create a virtual machine that would harmonize the differences between computer systems. The game file would always be the same for each system and there would be a system-specific interpreter program that would translate the game file into instructions the computer understood. This way the game could be programmed and compiled only once and it would work on any system that had an interpreter written for it.

The virtual machine was called Z-machine after Zork, the first game that used it. Decades later Inform 7 still compiles to Z-machine (and Glulx, the contemporary virtual machine that works basically the same way but with many of Z-machine's limitations removed).

To a modern consumer of interactive fiction the virtual machine model has other benefits in addition to being able to play the stories in a wide selection of devices. The virtual machine is effectively a sandbox that limits what story files are allowed to do. They can't, for example, delete files from the computer, install malicious software or access your webcam. When you download an interactive fiction story file you can be certain that it isn't a virus and it can't do anything harmful.

To an author of interactive fiction the sandbox can sometimes feel rather limiting. We've come a long way since the early days of Infocom and the things we now casually do with computers is far more than anyone could have dreamed of 30 years ago. Yet interactive fiction is still confined to streaming text, displaying pictures, playing sounds and performing some limited file operations.

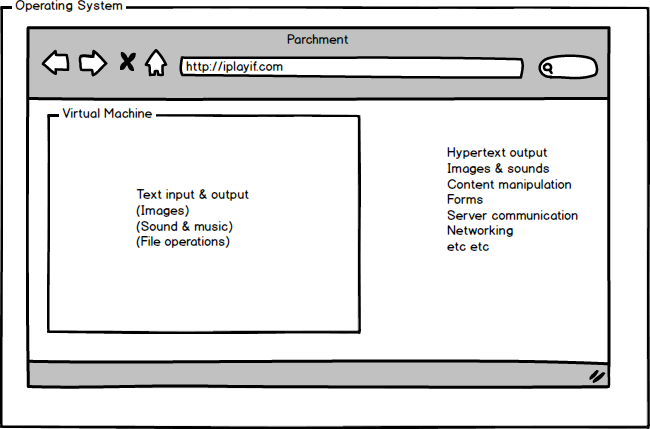

Cue the Internet age. A modern web browser is also a sandbox, but with quite a lot of more capabilities (but still with restrictions in place so that in theory you can visit any web page and be sure that you can't catch anything malicious).

Parchment, the first wide-spread web interpreter, was a small revolution in itself and turned the community focus from downloadable story files to Internet play, but Parchment and other Z-machine and Glulx interpreters are still "only" implementations of existing virtual machines. They restrict the story files to the same sandbox as offline interpreters do.

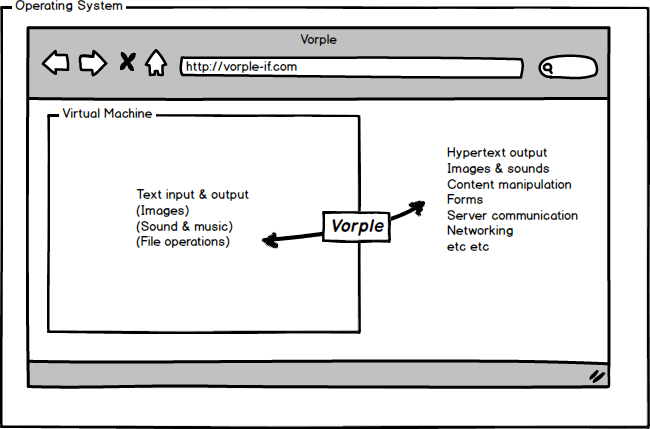

This is where Vorple comes in. It makes a small addition to the interpreter so that the story files can break free of the sandbox and communicate with the browser that's running the interpreter.

With this bridge in place the story file can do pretty much whatever it wants with the user interface and the story text — even story text that has already been printed.

Vorple's Inform extensions use this feature to interact with the interpreter, the browser and the JavaScript libraries bundled with the Vorple interpreter package. For example, the Vorple Tooltips extension issues commands to the PowerTip library that displays the actual tooltips.

To accomplish this, Vorple uses a virtual filesystem. When targeting Glulx, Inform story files have a limited file read and write capability. The story file writes the JavaScript code to a specifically named file, and the Vorple interpreter captures these file writes and instead executes the JavaScript code.

The story file uses a similar system to decide whether it's running in a Vorple interpreter. The interpreter provides a special (virtual) file for the Inform story to read. If the file exists and has the correct content, Vorple features can be enabled.